By Steven Horwitz

Nothing gets me going more than overt economic ignorance.

I know I’m not alone. Consider the justified roasting that Bernie Sanders got on social media for wondering why student loans come with interest rates of 6 or 8 or 10 percent while a mortgage can be taken out for only 3 percent. (The answer, of course, is that a mortgage has collateral in the form of a house, so it is a lower-risk loan to the lender than a student loan, which has no collateral and therefore requires a higher interest rate to cover the higher risk.)

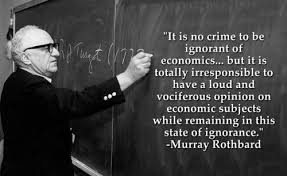

When it comes to economic ignorance, libertarians are quick to repeat Murray Rothbard’s famous observation on the subject:

It is no crime to be ignorant of economics, which is, after all, a specialized discipline and one that most people consider to be a “dismal science.” But it is totally irresponsible to have a loud and vociferous opinion on economic subjects while remaining in this state of ignorance.

Economic ignorance comes in different forms, and some types of economic ignorance are less excusable than others. But the most important implication of Rothbard’s point is that the worst sort of economic ignorance is ignorance about your economic ignorance. There are varying degrees of blameworthiness for not knowing certain things about economics, but what is always unacceptable is not to recognize that you may not know enough to be speaking with authority, nor to understand the limits of economic knowledge.

Let’s explore three different types of economic ignorance before we return to the pervasive problem of not knowing what you don’t know.

1. What Isn’t Debated

Let’s start with the least excusable type of economic ignorance: not knowing agreed-upon theories or results in economics. There may not be a lot of these, but there are more than non-specialists sometimes believe. Bernie Sanders’s inability to understand why uncollateralized loans have higher interest rates would fall into this category, as this is an agreed-upon claim in financial economics. Donald Trump’s bashing of free trade (and Sanders’s, too) would be another example, as the idea that free trade benefits the trading countries on the whole and over time is another strongly agreed-upon result in economics.

Trump and Sanders, and plenty of others, who make claims about economics, but who remain ignorant of basic teachings such as these, should be seen as highly blameworthy for that ignorance. But the deeper failing of many who make such errors is that they are ignorant of their ignorance. Often, they don’t even know that there are agreed-upon results in economics of which they are unaware.

2. Interpreting the Data

A second type of economic ignorance that is, in my view, less blameworthy is ignorance of economic data. As Rothbard observed, economics is a specialized discipline, and non-specialists can’t be expected to know all the relevant theories and facts. There are a lot of economic data out there to be searched through, and often those data require careful statistical interpretation to be easily applied to questions of public policy. Economic data sources also require theoretical interpretation. Data do not speak for themselves — they must be integrated into a story of cause and effect through the framework of economic theory.

That said, in the world of the Internet, a lot of basic economic data are available and not that hard to find. The problem is that many people believe that certain empirical facts are true and don’t see the need to verify them by actually checking the data. For example, Bernie Sanders recently claimed that Americans are routinely working 50- and 60-hour workweeks. No doubt some Americans are, but the long-term direction of the average workweek is down, with the current average being about 34 hours per week. Longer lives and fewer working years between school and retirement have also meant a reduction in lifetime working hours and an increase in leisure time for the average American. These data are easily available at a variety of websites.

The problem of statistical interpretation can be seen with data on economic inequality, where people wrongly take static snapshots of the shares of national income held by the rich and poor to be evidence of the decline of the poor’s standard of living or their ability to move up and out of poverty.

People who wish to opine on such matters can, again, be forgiven for not knowing all the data in a specialized discipline, but if they choose to engage with the topic, they should be aware of their own limitations, including their ability to interpret the data they are discussing.

3. Different Schools of Thought

The third type of economic ignorance, and the least blameworthy, is ignorance of the multiple perspectives within the discipline of economics. There are multiple schools of thought in economics, and many empirical questions and historical facts have a variety of explanations. So a movie like The Big Short that clearly suggests that the financial crisis and Great Recession were caused by a lack of regulation might be persuasive to people who have never heard an alternative explanation that blames the combination of Federal Reserve policy and misguided government intervention in the housing market for the problems. One can make similar points about the Great Depression and the difference between Hayekian and Keynesian explanations of business cycles more generally.

These issues involving schools of thought are excellent examples of Rothbard’s point about the specialized nature of economics and what the nonspecialist can and cannot be expected to know. It is, in fact, unrealistic to expect nonexperts to know all of the arguments by the various schools of thought.

Combining Ignorance and Arrogance

What is missing from all of these types of economic ignorance — and what is often missing from knowledgeable economists themselves — is what we might call “epistemic humility,” or a willingness to admit how little we know. Noneconomists are often unable to recognize how little they know about economics, and economists are often unable to admit how little they know about the economy.

Real economic “expertise” is not just mastery of theories and facts. It is a deeper understanding of the variety of interpretations of those theories and facts and humility in the face of our limits in applying that knowledge in attempting to manage an economy. The smartest economists are the ones who know the limits of economic expertise.

Commentators with opinions on economic matters, whether presidential candidates or Facebook friends, could, at the very least, indicate that they may have biases or blind spots that lead to uses of data or interpretive frameworks with which experts might disagree.

The worst type of economic ignorance is the type of ignorance that is the worst in all fields: being ignorant of your own ignorance.

Source: Foundation of Economics Education

No comments:

Post a Comment